One of the great mysteries of the universe is how things go from being inanimate to taking on the pulse and rhythm of life. It has long been a project of philosophers to understand where this transition occurs. Each of the shows I review today takes an aesthetic approach to identifying and understanding this transformation—not necessarily from the inanimate to the animate, but from a being merely material substance to being a part of the living, breathing world.

Chuck Close – Red, Yellow and Blue: The Last Paintings at Pace through April 13, 2024

One can instantly tell the difference between the face on wax sculpture and one on a living person. Even if the distance between the eyes and the color of the nose are exactly matched, one lacks a spark—an immediate, magical animation. Chuck Close’s paintings investigate why that is the case. The Pace Gallery is showing Red, Yellow, Blue: The Last Paintings—a collection of Close’s final paintings, including a few left unfinished at the time of his death. The title refers to a technique of stacking thinly painted layers of the primary colors, which ultimately bring the picture to life through their mixing. The exhibition text mentions that Close only started using this method towards the end of his life, even though he was clearly layering paint like this much earlier in his career. Some even think that his innovation of this style inspired the inventors of the inkjet printer, which constructs images through a similar process. The exhibition text rightly calls these paintings “conceptual” portraiture because they are hardly about the people represented. They are about what makes seeing a face, as opposed to any other object, a uniquely special experience. The grids of color and the printer-like technique turn the process of seeing a face from a magical one into a scientific one—recreating faces by meticulously assembling their constituent elements instead of in one blunt flash. Close had many neurological problems, and, of them, most attention has been given to his paralysis, which forced him to paint portraits in a grid to limit the necessity for dexterity with a paintbrush. But, in addition to his paralysis, Close was face blind (known officially as prosopagnosia) which disenabled him from recognizing faces. People with face blindness must learn to recognize faces in a similar way to how everyone else perceives wax faces—by memorizing who has a wider distance between their eyes or round versus pointed lips. Perhaps there could have been no other way for Close to paint portraits other than with this method. We, as viewers, get to learn how faces work alongside him, while he learns to approximate a faculty for facial recognition most of us take for granted.

Thomas Nozkowski – Everything in the World at Pace through April 20, 2024

Painter Thomas Nozkowski said, “Ultimately the one thing that a work of art is about, is the fact that a human being did it.” Knowing a painting was made by a human imbues it with a special significance, along with questions about intent and context. Moreover, humans alone (not cameras or AI) can perceive and recreate the subtle murmurs and trickles of life that we see with our own eyes, even in inanimate objects. Nozkowski’s paintings on display at Pace are a class-act in this endeavor. They are full of motion, created through a tense imbalance of forms and cascading marks. Even though these are abstract paintings, they almost feel representational—as if he was looking into some other realm and painting that. Some of the paintings feel like they depict what you would see if you were knocked out and your field of vision became flushed with spots and twinkles. Nozkowki’s paintings skillfully investigate the borderline between raw sense-data and ethereality. They could only have been made after spending hours staring at the world and pondering what makes it move.

Christopher Wool – See Stop Run in an abandoned office space at 101 Greenwich St through July 31, 2024

In an abandoned office space on the nineteenth floor of a building in the Financial District, which appears to have been attacked by a wrecking ball, is a collection of 60+ recent paintings and sculptures by Christopher Wool. If you walked in without knowing this was an art show, the only give-away would be the frames surrounding the paintings and the pedestals under the sculptures. The paintings are blotches of near-white paint on just off-white paper, which look strikingly similar to the adjacent swipes of paint on the bare plaster and cinder block walls. They look like the landlords who paint directly on top of light switches, gluing them in place, were suddenly struck by artistic inspiration. The sculptures are tortured tangles of wire, which look as if they’ve been ripped directly from the holes in the wall. They are contorted like once living wild animals—violently killed and taxidermied into their poses. In these works, Wool manages to find the aesthetic middle ground between industrial necessity and the hand of a practiced artist. The first step to appreciating them is knowing they were made by an artist instead of a construction worker. But once you realize that, you might never be able to tell the difference between them ever again.

Richard Prince – Early Photography, 1977–87 at Gagosian through April 13, 2024

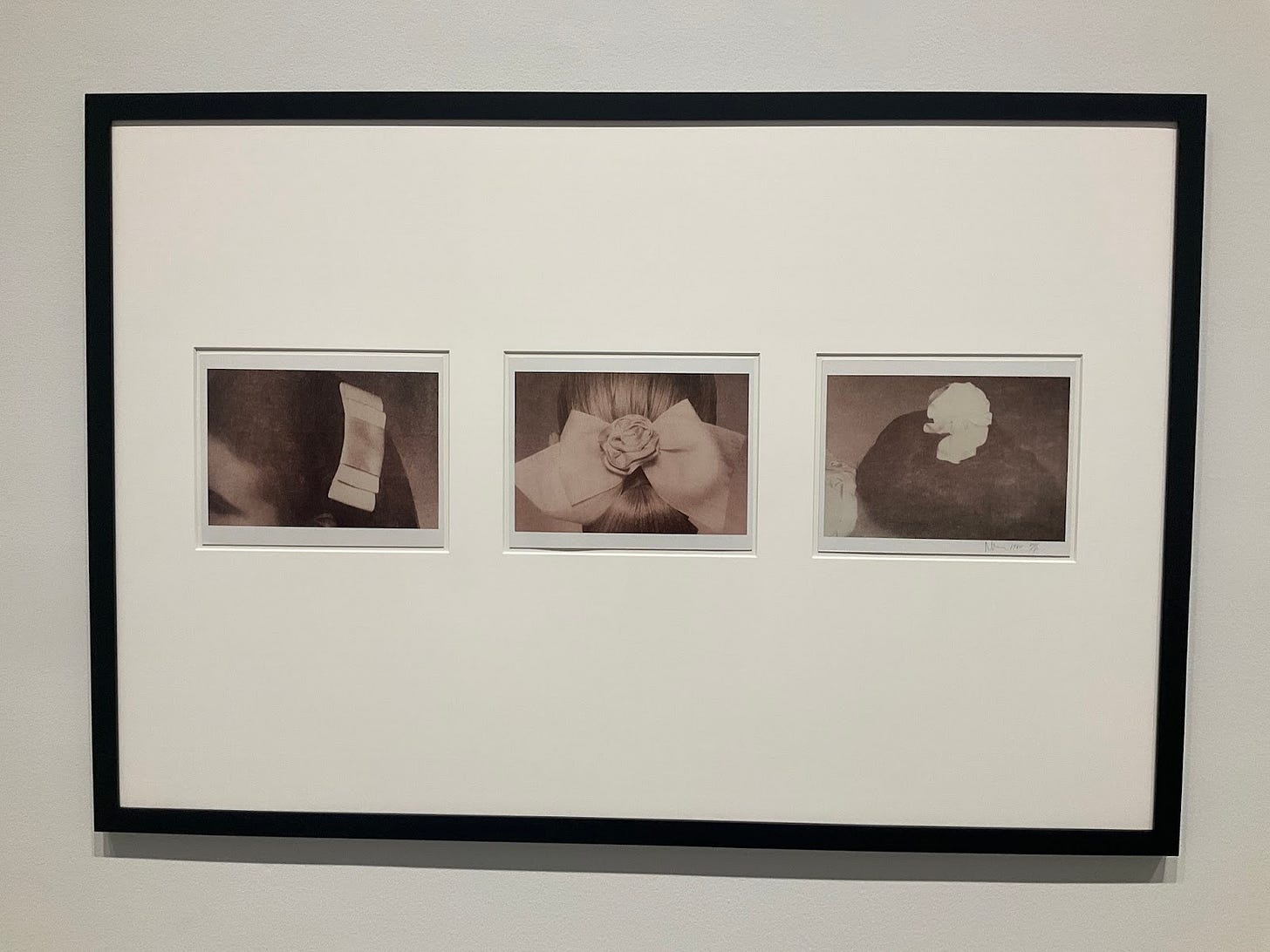

It is often said that one’s personality is the amalgamation of their five closest friends. I think that, similarly, we can say the world someone lives in is the amalgamation of their top five sources of media. Advertisements, TV shows, social media posts shape the parameters and arc we assign to the world. Gagosian’s exhibition of “re-photographs” (photos of photos) by Richard Prince brings this phenomenon to light by highlighting how American consumers, especially, obsess over images propagated by the media. Photos of wealthy homes are placed next to photos of Trix cereal and Kool-Aid. The fact that all these images have a similar aesthetic logic suggests that all niches of the consumer population are being tricked in the same way—with bright colors and striking compositions. A series of photos are cut off to only show women’s breasts and another bunch are cut off to focus only on bonnets, which suggest a Freudian obsession with singular body parts or clothing items. Photos of leather-jacketed biker gangs next to images of beautiful women indicate that we can be led to have paradoxically opposing desires: to be perfect but also rebellious and ragtag at the same time. The project of photographing images from magazines and newspapers brings a clinically observant eye to what influences our views of the power dynamics and desires that pulsate through the cultural landscape. Prince’s works are not merely photos of photos, but they are photos of a world with its own system of logic and values that lives in our heads, superimposed upon what we encounter when we walk outside.

Francesca Woodman at Gagosian through April 27, 2024

I don’t believe in ghosts, but Francesca Woodman’s exhibition at Gagosian makes a convincing case. In a series of small black and white photographs, Woodman portrays herself in a schizophrenic array of moods—sometimes naked, sometimes hiding, sometimes moving quickly across the room in a blur. Their small scale forces you to step up close to investigate. Looking at them can feel like peering through those Ghostbuster goggles that reveal paranormal activity. The exhibition text claims that she was inspired by “dilapidated interiors and ancient architecture:'' both places where people once lived, and where all that might remain is their ghostly presence. Ironically, Woodman seems to haunt herself, as if prefiguring her suicide at the age of 22. She often stands in the corner of a room, seemingly trying to hide in plain sight. Or she turns herself into a ghost by wearing a translucent sheet of plastic, obscuring her solid, physical presence in the world. In one picture, Woodman looks up at an ancient statue with her head tilted back and her arms stiff behind her, as if possessed by a satanic spirit. Whether by multiple personality disorder or by true possession, Woodman shows us a world that is ruled by much more than Newton’s laws alone.